Introduction:

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common type of Dementia, is a progressive neurodegenerative condition which is characterised by a gradual decline in memory and impaired daily activities. Early-onset Alzheimer’s presents with cognitive dysfunction, altered behaviour and changes in language and speech as primary symptoms. In this article we review Leqembi in Alzheimer’s Disease and challenges related to treatment access, cost barriers, and alleviating the burden faced by families and caregivers involved in the care of individuals with AD.

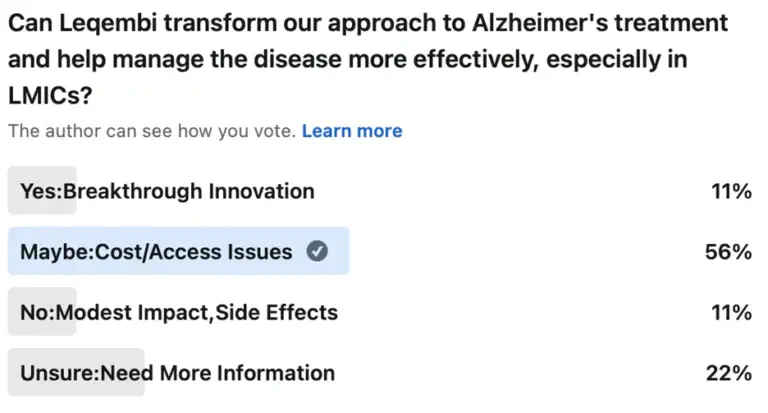

Dementia diagnoses occur at a staggering rate of one new case every three seconds globally, currently more than 55 million individuals reported to be living with dementia. [1] Projections indicate a significant escalation in these numbers, nearly doubling every two decades to 78 million by 2030 and 139 million by 2050, with a substantial portion of this increase anticipated in developing nations1. Currently, 60% of dementia cases are found in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). Moreover, LMICs will see a rise to 71% of dementia cases by 2050. As countries like China and India experience rapid growth in their elderly populations, addressing Alzheimer’s treatment is crucial.

Caregiver’s Perspective

Caring for individuals with AD and related dementias predominantly falls on the shoulders of family members and friends, with a staggering 80% receiving care within their homes. The study of the medical costs and caregiver burden sheds light on this impact. In the course of delivering five disease-modifying Alzheimer’s treatments with different durations and routes of administration, crucial aspects are often overlooked. When it comes to early Alzheimer’s diagnosis, oral drugs are a good therapy option. The oral treatment option not only is less costly but also minimises the number of clinic visits. Oral treatment costs just $1,983 with a minimal caregiver burden of $457, and it preserves a much higher 98% of the overall treatment value.

When comparing the costs and impacts of chronic bi-weekly infusion versus oral treatment, significant differences emerge. The chronic bi-weekly infusion is the most expensive option, with direct medical costs reaching $45,208 and a substantial caregiver burden of $6,095. To add further, it preserves only 56% of the overall treatment value. This stark contrast highlights not only the financial disparity but also the varying degrees of impact on caregivers and the effectiveness of treatment preservation between the two options.[2]

Role of Biomarkers in early AD diagnosis

Accurate diagnosis is essential for effective treatment, yet diagnosing diseases like AD can be complex due to the subtle and overlapping nature of its symptoms. Biomarkers are crucial for diagnosing and managing AD, offering deep insights into its underlying pathology. Key biomarkers such as beta-amyloid (Aβ) and tau proteins can be detected through cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis and advanced imaging techniques like positron emission tomography (PET). Furthermore, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is pivotal in identifying brain atrophy, particularly in the hippocampus, which is one of the first regions affected by AD. MRI also helps in evaluating whole brain and ventricular volumes, providing valuable information on neurodegeneration and disease progression. [3]

Biomarkers facilitate early Alzheimer’s detection, often years before symptoms appear, and help differentiate it from other dementias. The National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) guidelines use these biomarkers to refine diagnostic criteria, improve accuracy, and guide treatments. They are essential for monitoring disease progression and assessing treatment efficacy in clinical trials. [3]

Current treatment approaches for AD

AD symptoms can be managed to maintain patient independence and support carers. Cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine) alleviate behavioural and cognitive issues by preventing acetylcholine breakdown. For moderate-to-severe cases, memantine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist, helps by controlling glutamate and preserving brain cells.

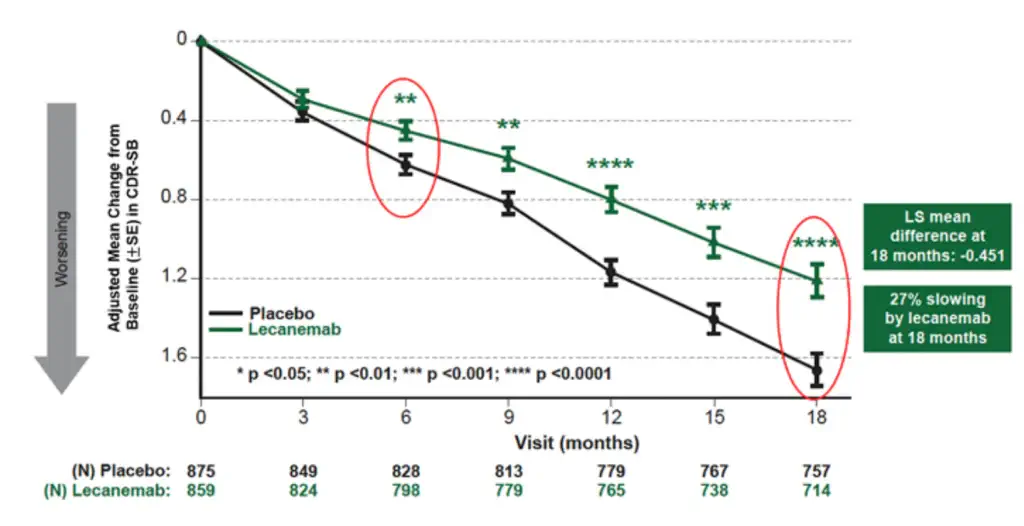

An immune therapy approved by the FDA for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s in the United States is lecanemab. [4] It works by reducing beta-amyloid protein, which is one of the main brain abnormalities associated with AD. Lecanemab’s efficacy was evaluated in clinical trials exclusively on patients with mild cognitive impairment or early-stage AD. According to study findings, lecanemab decreased brain amyloid levels and slowed the rate of cognitive deterioration in study participants during an 18-month period.

Global Economic Burden of Dementia

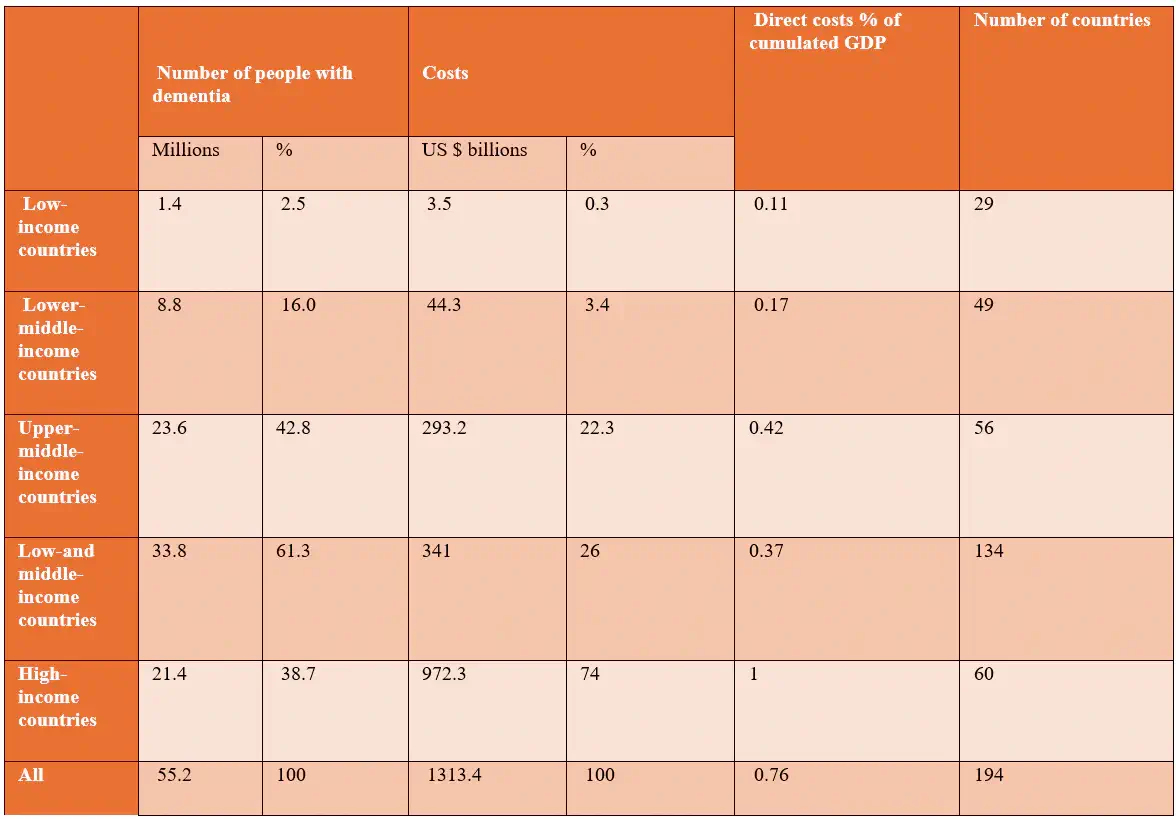

AD accounts for 60–70% of cases and the financial burden associated with dementia extends beyond medical expenses to encompass significant social costs. Table 2 estimates that the global direct medical costs, including hospitalisations, prescription medications, and diagnostic tests, amounted to $213.2 billion in 2019. [5] This represents a substantial portion of the overall financial impact of dementia. Direct social costs, covering residential care, long-term services, and community support, totaled $448.7 billion, reflecting the extensive resources required for non-medical care. Furthermore, unpaid care provided by family and friends contributed an estimated $651.4 billion in lost productivity. The total societal cost of dementia in 2019 was a staggering $1,313.4 billion, averaging $23,796 per dementia patient globally. These figures underscore the immense financial strain that dementia imposes on both formal healthcare systems and informal caregiving networks. [5]

Table 1: Estimated Worldwide Costs of Dementia in 2019 (billion US $), Based on Current World Bank Classification 2019

Comparative effectiveness of Leqembi in Alzheimer’s

The effectiveness of lecanemab in conjunction with supportive care as opposed to supportive care alone has generated a great deal of attention in the field of AD treatment. A recent study examines the clinical effects of lecanemab, a medication that may improve the treatment of early AD. Analysing data from the CLARITY AD trial, which targeted people with early AD pathology, the research evaluated several outcomes, such as biomarker changes, quality of life, and cognitive function. Specifically, at 18 months, lecanemab showed a 27% decrease in the decline in the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale-Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) as compared to a placebo (Figure 2). Individuals on lecanemab showed a reduced reduction in health-related quality of life and reduced the burden on caregiver. [6]

In Figure 2, with statistically significant reductions in the CDR-SB score, the medication appears to be more successful in younger patients (less than 65), ApoE ε4 positive individuals, and both male and female patients. Moreover, the ApoE ε4 gene variant significantly increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and helps predict how well a patient might respond to the treatment. In ApoE ε4 negative patients, the effect is less prominent and not statistically significant. This comprehensive analysis aids doctors and researchers in making more tailored treatment decisions by integrating lifestyle modifications, cognitive assessments, biomarker testing, and supporting ongoing research to identify patient subgroups most likely to benefit from the treatment. [6]

Long term effectiveness of Leqembi in Alzheimer’s

The cost-effectiveness of lecanemab compared to supportive care in AD treatment reveals notable financial metrics. Lecanemab has incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) of $277,000 per life year gained, $254,000 per Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY) gained, and $204,000 per Equal Value Life Year (evLY) from the healthcare sector’s perspective. Societal ICERs are slightly better, with $265,000 per life year gained, $236,000 per QALY gained, and $183,000 per evLY. Sensitivity analyses confirm these figures, with ICERs of $248,000 per QALY and $200,000 per evLY. In a modified socioeconomic analysis, lecanemab costs $790,000 and yields 3.49 QALYs and 3.64 evLYs, while supportive care costs $670,000 for 2.98 QALYs and evLYs. Updated caregiver disutility estimates show lecanemab costs $265,000 per life year gained, $213,000 per QALY, and $163,000 per evLY, underscoring its financial impact and potential benefits. [6][7]

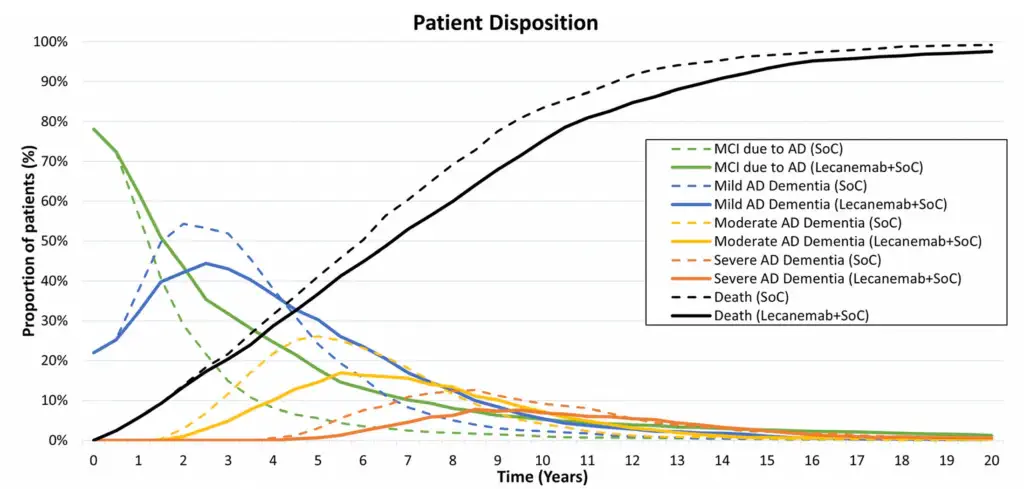

Another study analysing lecanemab’s impact found that combining the drug with standard of care (SoC) provided substantial long-term benefits for patients with early AD. The base-case analysis showed a 0.75 gain in QALYs and a delay in progression to AD dementia by 2.51 years. In addition, patients on lecanemab + SoC spent 11.6 more years in community care and 0.13 fewer years in institutional care, with an overall survival gain of 1.03 years. Scenario analyses further demonstrated that initiating lecanemab at a median age of 65 years resulted in an additional 0.23 QALYs over a lifetime, with benefits increasing over time. Overall, Figure 3 highlights that lecanemab + SoC significantly delays disease progression and improves quality of life compared to SoC alone. [8]

Patients Reported Outcomes and Quality Adjusted Life Years

Lecanemab’s budget impact analysis for Alzheimer’s illness shows that the healthcare system will be heavily impacted monetarily. Based on an estimated 1.4 million eligible patients in the United States and a 20% yearly treatment initiation rate, the potential budgetary impact per patient in the first year would be about $27,000, and over the course of five years, it would be about $104,000. [6] For new medications, the five-year annualised prospective budget impact threshold is set at $777 million annually. [6]

Only roughly 5% of the eligible population could receive treatment within this threshold at the present cost of $26,500 annually. However, 9% of the population could receive treatment if the cost-effectiveness barrier is raised to $150,000 per QALY, and up to 59% could receive treatment if it is reduced to $50,000 per QALY. [6] The access and affordability notice warn of unsustainable budget impact, stressing the crucial balance between availability and affordability of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s patients.

Conclusion

The introduction of lecanemab indeed marks a significant milestone in the treatment of AD. This is true articularly for LMICs where the burden of neurodegenerative diseases is substantial. Lecanemab slows the decline in cognitive function and daily activities by targeting and reducing amyloid levels effectively. This represents a shift towards disease modification rather than just symptom management. [9] Also, lecanemab has been linked to a reduction in caregiver burden, highlighting its potential impact.

However, the high costs and potential adverse events, such as Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities (ARIA) and infusion-related reactions, have contributed to a slower approval process in other countries. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) denied its marketing authorisation in the EU. [10] To address these challenges, strategies such as value-based pricing, expanded insurance coverage, rigorous patient monitoring, and enhanced patient education should be implemented. These measures can help optimise the cost-effectiveness of lecanemab, ensuring that its benefits in terms of QALYs are maximised while minimising both financial and clinical risks.

References

- Dementia. (2023, March 15). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

- Ozawa, T., Franguridi, G., & Mattke, S. (2024). Medical Costs and Caregiver Burden of Delivering Disease-Modifying Alzheimer’s Treatments with Different Duration and Route of Administration. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer S Disease. https://doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2024.81

- Jack, Clifford R Jr et al. “Comparison of plasma biomarkers and amyloid PET for predicting memory decline in cognitively unimpaired individuals.” Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association vol. 20,3 (2024): 2143-2154. doi:10.1002/alz.13651.

- Van Dyck, C. H., Swanson, C. J., Aisen, P., Bateman, R. J., et. al. (2023c). Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 388(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2212948

- Wimo, A., Seeher, K., Cataldi, R., Cyhlarova, E., et. al. (2023). The worldwide costs of dementia in 2019. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 19(7), 2865–2873. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12901

- Lin GA, Whittington MD, Wright A, Agboola F, Herron-Smith S, Pearson SD, Rind DM. Beta-Amyloid Antibodies for Early Alzheimer’s Disease: Effectiveness and Value; Evidence Report. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, April 17, 2023. https://icer.org/assessment/alzheimers-disease-2022/#timeline

- Wright, A. C., Lin, G. A., Whittington, M. D., Agboola, F., Herron-Smith, S., Rind, D., & Pearson, S. D. (2023). The effectiveness and value of lecanemab for early Alzheimer disease: A summary from the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review’s California Technology Assessment Forum. Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, 29(9), 1078–1083. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2023.29.9.1078

- Monfared, A. a. T., Ye, W., Sardesai, A., Folse, H., Chavan, A., Aruffo, E., & Zhang, Q. (2023). A Path to Improved Alzheimer’s Care: Simulating Long-Term Health Outcomes of Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease from the CLARITY AD Trial. Neurology and Therapy, 12(3), 863–881. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-023-00473-w.

- Frederiksen, K. S., Arus, X. M., Zetterberg, H., et. al. (2024b). Focusing on earlier diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Future Neurology, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.2217/fnl-2023-0024

- Hicks, R. (2024, July 26). EMA Refuses Marketing Authorization for Alzheimer’s Drug. Medscape. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/ema-refuses-marketing-authorization-alzheimers-drug-2024a1000dsw?form=fpf

Table of Contents