Panel Theme

“Together for Access to Innovative Treatments.” 20 June 2022.

Organizer

Todos Juntos Contra on Cancer (TJCC). TJCC is composed of more than 200 institutions from different sectors engaged in improving cancer care in Brazil and aims to improve policies for Oncology. https://tjcc.com.br/

Panelists

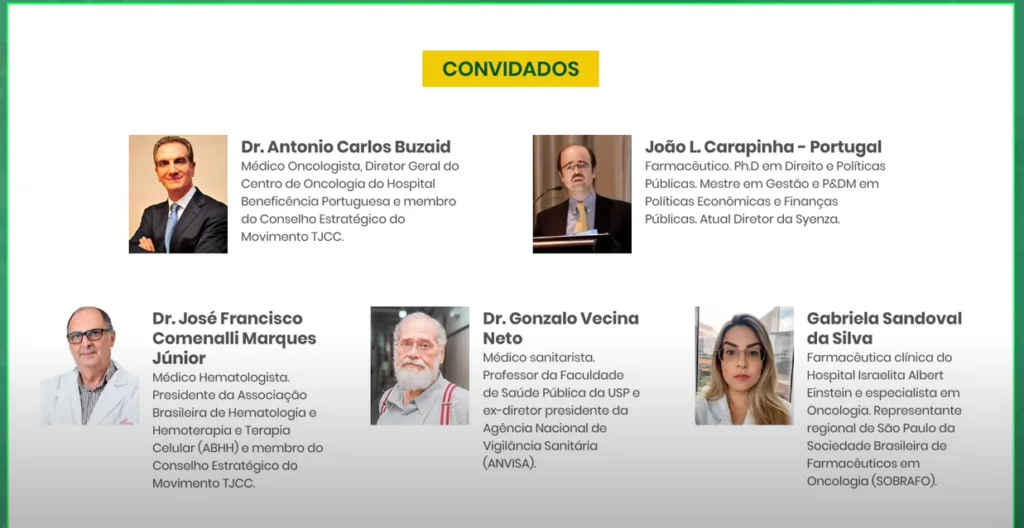

- Prof. João L. Carapinha

- Dr. Antonio Carlos Buzaid

- Dr. José Francisco Comenalli Marques Júnior

- Dr. Gonzalo Vecina Neto

- Gabriela Sandoval da Silva

Panelists (click image to view video on YouTube)

Translated Transcript of Prof. João Carapinha’s presentation

Good afternoon everyone, thanks so much for joining me for this presentation this afternoon. Before I get started, I’d like to thank the organisers for the invitation to share a few thoughts over the next 10 minutes about access to new healthcare technologies, from a European perspective. It’s a pleasure to support TJCC in all of its activities in Brazil and it is my absolute pleasure to be amongst a group of expert panellists to contribute to this important topic.

Given that this presentation is only approximately 10 minutes duration, I would like to address four important themes in the time that we have available. These include:

- The development of new healthcare technologies is a lengthy and expensive process.

- Government agencies in Europe have established systems to evaluate new healthcare technologies.

- Access to new healthcare technologies depends on investments in our future health.

- Patients have an essential role in improving current systems.

Panelists (click image to view video on YouTube)

On the first theme, the development of new medicine before it comes to the market can take between 10 to 15 years before the regulatory agency approves it. The figure in front of you right now illustrates the different phases of clinical research that are involved in bringing a new drug to the market. Notice that during the drug discovery phase, there are usually between 5000 to 10,000 compounds which are actively being researched and screened as potential options for further investigation. Only 250, approximately, of those compounds move into the preclinical phase, which are compounds that show some promising effects and that may be efficacious in human use. After screening these compounds for further potential to meet the minimum regulatory standards, only five will reach the clinical trial phase, which can run between 6 to 7 years and may involve several thousands of patients around the world. Typically, this phase is divided into Phase 1, Phase 2, and Phase 3, all of which combined address the safety, quality, and efficacy of the proposed compound for a specific therapeutic area. Not all clinical trials are successful and of the five that entered the clinical trial phases, only one is submitted for approval by the regulatory agency and is finally approved and made commercially available in the market. After that, they may market the originator product under a patent for a defined period.

The key issue to consider in looking at all these steps related to bringing a new medication to market is the significant cost of doing so. The cost of all the promising compounds that failed during the drug discovery phase, preclinical phase and clinical trial phases are carried partly by the price set for the one medication that was approved by the regulatory agency. The efficiency with which pharmaceutical companies and biotechnology companies undergo this process will determine how efficiently new medicines come to the market, their prices, and the level of competitiveness in each individual market. This point on the price of a new medication is controversial, not only in Brazil but in many international markets. The key question to address is how public healthcare systems and consumer-based markets reward and provide incentives to private investors for taking the risk of developing new medicines and making them available for regulatory approval. The other key question is related to how regulatory agencies support the market in improving the speed with which new medicines are made available to the public.

The second theme that I’d like to address is the role of government agencies (specifically health technology assessment agencies) and their role in the economic evaluation of new healthcare technologies. The steps that I’ll be talking about here are seldom done in parallel with the regulatory approval of new healthcare technologies, but are typically done after their regulatory approval. Meaning that this adds additional months and sometimes years to the final approval and funding of new healthcare technologies in international markets. The two images that I’m displaying at the moment represent functional parts of a regulatory system in England and France that evaluate the safety, quality, and efficacy of new healthcare technologies but also the economic value of new treatments.

Panelists (click image to view video on YouTube)

With France, the regulatory approval of new medicines is done by the European Medicines Agency, which functions on behalf of the European Commission and executes the market authorization function. The second step involves engaging the health technology assessment agency (HAS) which does an evaluation of the therapeutic value, the budget impact, and the cost effectiveness of new healthcare technologies. HAS interfaces with other government agencies in France, such as the Ministry of Health, the social security system, and also the pricing authority. Only once passing through each of these organizations are patients able to access new healthcare technologies paid for by the government. Similarly, in England, there are various internal government institutions such as the Department of Health, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, the Pharmaceutical Price Regulatory Scheme, and others that are similarly responsible for evaluating new healthcare technologies.

The key issues in comparing health technology assessment systems is duplication. The medicine submitted to French agencies versus English agencies versus agencies in Brazil is precisely the same, however there is a tremendous amount of duplication in effort and wasted taxpayer funds to produce reports that would be no different if it came from the same source. An initial clinical evaluation in France, England, Brazil, Russia, and South Africa, for example, would not be very different other than the need to adapt local epidemiological information and perhaps genetic differences in populations. But the therapeutic value would not change.

Removing this duplication between systems and applying this insight in Brazil would be a key next step in the future. Brazil has already set up an extensive unified healthcare system which has been running for decades. Compared to other middle-income countries, it has been quite successful, although there are still areas to continuously improve. The evaluation of new healthcare technologies through CONITEC with support from other government agencies is a key function that enables access to new healthcare technologies. How efficient are these government agencies in executing their roles? Could their timelines be potentially shortened? Are delays in funding new healthcare technologies potentially causing harm to many patients. What could be done to make the systems more efficient?

Finding a new medication that meets the regulatory standards of being safe, of good quality, and efficacious in human use is an important barrier. The next critical barrier is passing through an economic evaluation coordinated by health technology assessment agencies. All the investments by private investors and government agencies into building efficient processes will affect the health of future generations. If new breakthrough therapies that significantly alter the natural course of disease are not discovered and are not rapidly approved by government agencies, then improvements in a patient’s quality of life will be significantly impaired.

The final theme that I would like to comment on is that patients individually and organised through formal structures (such as TJCC) play a critical role in improving the drug development process and also the efficiency of health technology assessment agencies. Patients play a critical role in priority setting to direct investments into key therapeutic areas where a significant unmet need remains. Patients should be formally integrated into decision-making structures in government agencies when new healthcare technologies are being evaluated. Regrettably, very few international health technology assessment agencies have competently integrated patient associations into their decision-making process. This is an area for further development.

In closing, thank you very much for listening. If you have any follow-up questions, please reach out on our contact form or visit our webpage where we have plenty of background information on the different methods utilized in economic evaluations and also key topics related to health technology assessment.

Thank you.

Table of Contents