Introduction

Many middle-income countries such as Egypt, South Africa, Malaysia, Thailand, and Brazil have established pharmacoeconomic guidelines. These guidelines are based on the recommendations by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) all with distinct country-specific variations. These variations respond to changes in how governments apply pharmacoeconomics in middle-income countries and determine market access to pharmaceuticals and medical devices. This is also determined by differences in healthcare structure, disease area priorities, and sociopolitical preferences.

This Insight Article seeks to explore three research questions:

- What are the principal characteristics and differences among pharmacoeconomic guidelines?

- How do health technology assessments (HTA) in high-income countries impact market access of pharmaceutical products?

- What are the challenges associated with applying pharmacoeconomics in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) such as South Africa?

To address these questions, we undertake a review of the pharmacoeconomic guidelines in South Africa as a basis to compare with other global counterparts including the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in England. We also critically examine the function of the HTA bodies in middle income countries and the influence high income countries have in global HTA. Lastly, we identify and analyse key themes relevant to our paper.

What are the Main Features and Differences Among Pharmacoeconomic Guidelines?

A study by Marsh and Truter compared the South African Guidelines for Pharmacoeconomic Submissions (SAGPS) with guidelines from Egypt and England using the EUnetHTA HTA Core Model framework. The results showed that the SAGPS focused more on the economic aspects of HTA, with less consideration for legal, social, and ethical implications. On the other hand, the NICE guidelines are more extensive and cover a broader range of issues, including safety, patient and societal aspects, and ethical considerations. The NICE guidelines also allow participation by healthcare providers and patients and direct the Appraisal Committee to make societal value judgements based on respect for autonomy, individual choice, avoiding discrimination, and promoting equality. [1]

A comparative analysis of pharmacoeconomic guidelines by Carapinha et al, [2] compared the key features of the pharmacoeconomic guidelines in South Africa with other countries. This study selected five upper middle-income countries (Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Malaysia, and Mexico), one lower middle-income country (Egypt), and six high-income countries (Germany, Ireland, Norway, Portugal, Taiwan, and the Netherlands).

The primary focus was to interpret the distinct characteristics and potential disparities in the pharmacoeconomic guidelines of South Africa in relation to these countries:

Perspective and Costs

- South Africa’s pharmacoeconomic guidelines are limited to the private healthcare sector and a third-party payer perspective.

- Private healthcare expenditure in South Africa is the highest among middle and high-income countries as a proportion of gross domestic product.

- The focus on the private sector may limit the usefulness of pharmacoeconomic evaluations intended to contain medicine expenditure and regulate medicine reimbursement prices.

- The guidelines do not address the equitable distribution of cost-effective health technologies in South Africa.

Modelling

- South Africa is the only country that requires an application to develop a model before conducting a pharmacoeconomic evaluation.

- The guidelines discourage the use of complex models and prefer simple ones. This approach may lead to the development of models that do not accurately represent the reality of local practice conditions.

- The preference for simple models may be linked to the poor quality of health economics studies in South Africa.

Equity Issues Stated

- The guidelines do not discuss equity issues or how quality-adjusted life years should be valued across the population.

- The focus on the private healthcare sector may perpetuate inequities in South Africa’s dual healthcare system.

- The guidelines do not align with the broader equity objectives of the National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill.

Financial Impact Analysis

- Private health insurance companies in South Africa are not required to publish reimbursement data.

- The lack of available data makes it challenging to perform a budget impact analysis.

- This is in contrast to other countries where a budget impact analysis is either required or recommended.

Mandatory, Recommended, or Voluntary Submissions

- Pharmacoeconomic submissions are only recommended or voluntary in middle-income countries, unlike in high-income countries where they are mandatory.

- Factors such as lack of adequately trained staff, narrow focus on the private sector, and lack of financial resources may inhibit the implementation of mandatory submissions in South Africa.

- The guidelines note that the findings of the assessment are not binding and no provision has been made for the appeals process, which may discourage submissions by pharmaceutical companies. [2]

How do Health Technology Assessments in High-Income Countries Impact Pharmaceutical Market Access?

The Emergence and Evolution of HTA

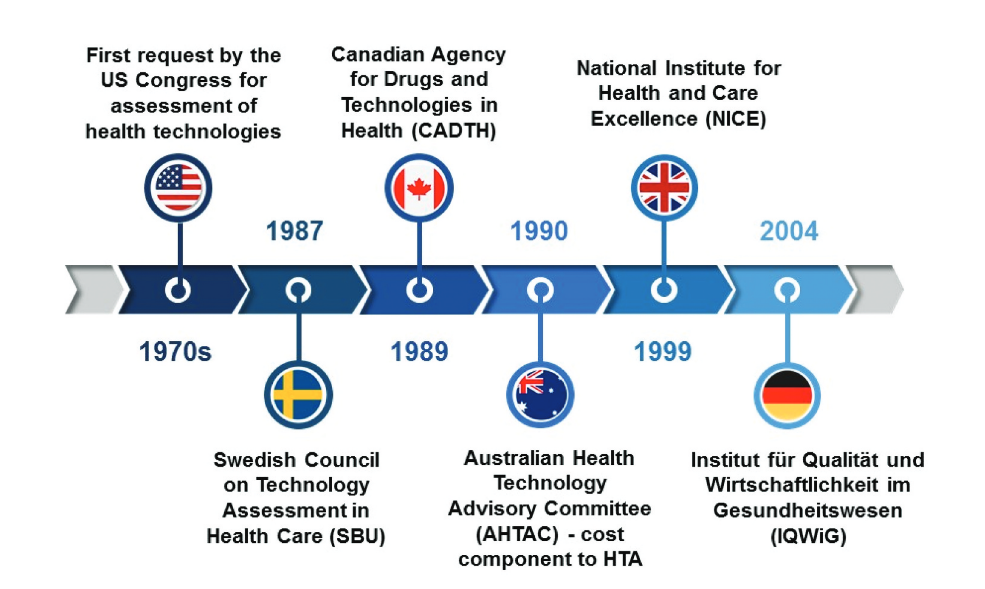

At the request of Congress, HTA initially appeared in the United States in the 1970s. This term, now internationally recognised, gained traction primarily in wealthier nations that prioritised the assessment and enhancement of healthcare in the face of rising expenditures and the deployment of unproven technologies. The 1990s marked a period of HTA institutionalisation in Europe and other regions. The Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU), established in 1987, was the first national agency of its kind. It was followed by the formation of the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) in 1989, a rebranding of the Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment (CCOHTA). Australia led the world in integrating a cost component into HTA decisions in the early 1990s.

Global Adoption and Institutionalisation of HTA

Many countries globally now have well-established HTA processes at the national level, primarily in high-income countries. The United Kingdom established NICE in 1999 to reduce disparities in the availability and quality of treatments in the National Health Service (NHS). Germany introduced the Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen (IQWiG) in 2004. These HTA bodies support a range of health decisions, from the implementation of extensive public health programs to the development of clinical guidelines. However, the role and application of HTA vary significantly due to the differing cultural, historical, political, and healthcare financing contexts. As the demand for efficiency and value in healthcare escalates, more local health authorities, hospitals, and other healthcare organisations are requesting HTA. Countries are continually enhancing transparency, accountability, and knowledge sharing in HTA, with numerous international networks and collaborations existing among countries and their HTA bodies. [3]

The Use of HTA in Regulatory, Coverage, and Reimbursement Decisions

HTA serves as a structured approach to analysing healthcare technologies, providing essential input for regulatory, coverage, and reimbursement policy decisions. As a health technology itself, HTA acts as a process technology for making resource allocation decisions, varying in sophistication levels. HTA can be categorised into ‘micro’ HTA, focusing on incremental technologies such as drugs and devices, and ‘macro’ HTA, which concentrates on the overall framework of the health system, including the number and mix of healthcare facilities and health workers. [4]

The Importance and Challenges of HTA in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

In the context of LMICs, the role of HTA is pivotal, despite the challenges these countries face. With limited healthcare budgets, LMICs often grapple with prioritising healthcare needs and directing investments in health technologies. As the global health pipeline continues to produce new medicines and vaccines intended for LMICs, the role of HTA will become even more significant. Enhancing institutional and human resource capacity for HTA can lay the groundwork for the product development partnerships needed for successful evaluation and adoption of innovative technologies in LMICs.

However, the implementation of HTA in low-income countries faces numerous challenges, including a lack of local data, limited technical expertise, and weak or non-existent local institutions with the capacity to conduct HTA. [4] LMICs are also faced with a politicised decision-making process where decisions often shift to higher political levels where budget constraints and political considerations may outweigh analytical approaches. This can lead to a focus on budget impact at the expense of other important factors, introducing a dysfunctional bias into the application and interpretation of HTAs. This lack of reliable data makes it difficult to adapt international pharmacoeconomics models from high income countries for new pharmaceutical products to support reimbursement decision making effectively in LMICs. [5] Despite these obstacles, there is a growing interest in HTA in LMICs, albeit with varying levels of institutional development and limited application in making regulatory, coverage, and reimbursement decisions. [4]

Challenges with Applying Pharmacoeconomics in Middle-Income Countries such as South Africa

The Disconnect Between Public and Private Sectors in Guideline Development

The healthcare industry in South Africa functions in a setting that is severely lacking in resources and is organised in a complicated two-tier structure. About 16% of the population is covered by private health insurance, while the vast majority of people are insured by the public sector, which is supported by funding from both the government and individual provinces. As a consequence of this, there are considerable disparities across the nation in terms of healthcare costs, demand, financing systems, benefit packages, and incentive programs.

The private healthcare industry has been characterised by high and rising prices of healthcare and medical scheme cover, as well as significant overutilisation without stakeholders demonstrating associated improvements in health outcomes. Moreover, the costs of healthcare and medical scheme cover have been increasing. A recent inquiry conducted by the Competition Commission found that one of the problems that need to be addressed is the absence of open and standardised procedures that can be used to measure and compare the cost-effectiveness of various healthcare therapies.

Implications for the Future of South African Healthcare System

When it comes to incorporating sound clinical and economic evidence into healthcare decision-making, the healthcare industry in South Africa is up against a number of daunting obstacles. Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) are helpful tools that can aid in the making of transparent decisions on healthcare. These guidelines are influenced by systematic reviews of the available clinical and economic data. However, the production of these guidelines is currently disjointed. There is no formal coordination between the public sector and the private sector in terms of topic selection, methodological approaches, reporting standards, or implementation strategies. This is a concern because all of these parts of developing these recommendations are critical.

South Africa is contemplating a series of reforms over the next few decades to introduce Universal Health Coverage. These reforms will be implemented through the NHI that has been proposed. The goal is to enhance the level of care that is provided by the public sector and to better coordinate the delivery of health services provided by the public sector and the private sector. Despite this, it is still difficult to produce CPGs that are based on the strongest available clinical and cost-effectiveness data.

Several factors affect the type of health economic evidence that is made and how much it is used in the creation of CPGs. These factors include the type of intervention, the availability of data, and the technical skills of both those putting together the evidence and those who need to use it. Because of this, the South African healthcare system, which is working to enhance both the quality and the efficiency of care, faces some particularly difficult problems. [6]

Key Takeaways on Pharmacoeconomics in Middle-income Countries

- When compared to high-income countries, pharmacoeconomics in middle-income countries, particularly South Africa, has distinct characteristics and face unique obstacles. These include an emphasis on the private sector, a preference for simplistic models, and a lack of data availability for financial impact analysis.

- HTAs play an important role in pharmaceutical product market access in high-income nations. However, in middle-income countries, its acceptance and implementation may be hampered by a lack of local data, limited technical skills, and insufficient institutional capacity.

- South Africa’s healthcare system is divided into two tiers, with major inequalities in healthcare expenditures, demand, financing mechanisms, and incentive programs. This duality, combined with high and rising healthcare costs, presents significant obstacles for the use of pharmacoeconomics.

- The effective implementation of NHI is critical to the future of South Africa’s healthcare system. However, developing clinical practice guidelines based on substantial clinical and cost-effectiveness evidence remains difficult due to factors such as intervention type, data availability, and stakeholders’ technical skills.

References

- Marsh SE, Truter I. The South African Guidelines for Pharmacoeconomic Submissions’ Evidence Requirements Compared with Other African Countries and The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in England. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2020 Apr;20(2):155-168. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2019.1615451. Epub 2019 May 22. PMID: 31056961.

- Carapinha JL. A comparative review of the pharmacoeconomic guidelines in South Africa. J Med Econ. 2017 Jan;20(1):37-44. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2016.1223679. Epub 2016 Aug 26. PMID: 27564849.

- Falkowski A, Ciminata G, Manca F, Bouttell J, Jaiswal N, Farhana Binti Kamaruzaman H, Hollingworth S, Al-Adwan M, Heggie R, Putri S, Rana D, Mukelabai Simangolwa W, Grieve E. How Least Developed to Lower-Middle Income Countries Use Health Technology Assessment: A Scoping Review. Pathog Glob Health. 2023 Mar;117(2):104-119. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2022.2106108. Epub 2022 Aug 10. PMID: 35950264; PMCID: PMC9970250.

- Joseph B Babigumira, Alisa M Jenny, Rebecca Bartlein, Andy Stergachis, Louis P Garrison, Health technology assessment in low- and middle-income countries: a landscape assessment, Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research, Volume 7, Issue 1, March 2016, Pages 37–42, https://doi.org/10.1111/jphs.12120

- Dankó D. Health technology assessment in middle-income countries: recommendations for a balanced assessment system. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2014 Mar 11;2. doi: 10.3402/jmahp.v2.23181. PMID: 27226832; PMCID: PMC4865748.

- Wilkinson, M., Hofman, K.J., Young, T. et al. Health economic evidence in clinical guidelines in South Africa: a mixed-methods study. BMC Health Serv Res 21, 738 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06747-z

Table of Contents